Israel – United States relations

|

|

|

|

| United States | Israel |

Israel – United States relations are an important factor in the United States government's overall policy in the Middle East. The United States Congress places considerable importance on the maintenance of a close and supportive relationship with Israel. The main expression of Congressional support for Israel has been foreign aid, with Israel being the largest recipient of US aid from 1976 to 2004;[1] Aid to Israel has been surpassed by aid to Iraq, following the 2003 invasion. Congress monitors this aid closely, along with other issues in bilateral relations. Congressional concerns have affected different administrations' policies over the last 60 years.

Bilateral relations have evolved from an initial US policy of sympathy and support for the creation of a Jewish homeland in 1948 to an unusual partnership that links a small but militarily powerful Israel, dependent on the United States for its economic and military strength, with the US superpower trying to balance competing interests in the region. Some in the United States question the levels of aid and general commitment to Israel, and argue that a US bias toward Israel operates at the expense of improved US relations with various Arab and Muslim governments. Others maintain that Israel is a strategic ally, and that US relations with Israel strengthen the US presence in the Middle East.[2] Israel is one of the United States' two original major non-NATO allies in the Middle East. Currently, there are seven major non-NATO allies in the Greater Middle East.

Attitude toward the Zionist movement

The Christian belief in the return of the Jews to the Holy Land has deep roots, which pre-date both the establishment of Zionism and the establishment of Israel. Support for Zionism among American Jews was minimal however, until the involvement of Louis Brandeis in the Federation of American Zionists,[3] starting in 1912 and the establishment of the Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist Affairs in 1914; it was empowered by the Zionist Organization ‘to deal with all Zionist matters, until better times come.”[4]. The British Balfour Declaration of 1917 both advanced the Zionist movement of the time and gave it official legitimacy.

While Woodrow Wilson was sympathetic to the plight of Jews in Europe, he repeatedly stated in 1919 that U.S. policy was to "acquiesce" in the Balfour Declaration but not officially support Zionism.[5] The US Congress however passed the Lodge-Fish resolution,[6] the first joint resolution stating its support for "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people" on September 21, 1922.[7][8] The same day, the Mandate of Palestine was approved by the Council of the League of Nations. Despite two similar attempts by Congress during the war, the policy of acquiescence continued until after WWII.

During the war, US foreign policy decisions were often ad hoc moves and solutions dictated by the demands of the war. At the Biltmore Conference in May, 1942, the Zionist movement made a fundamental departure from traditional Zionist policy and its stated goals,[9] with its demand "that Palestine be established as a Jewish Commonwealth."[10]

Following the war, the “new postwar era witnessed an intensive involvement of the United States in the political and economic affairs of the Middle East, in contrast to the hands-off attitude characteristic of the prewar period. Under Truman the United States had to face and define its policy in all three sectors that provided the root causes of American interests in the region: the Soviet threat, the birth of Israel, and petroleum.”[11]

Recognition of the State of Israel

Previous American presidents, although encouraged by active support from members of the American and world Jewish communities, as well as domestic civic groups, labor unions, political parties, supported the Jewish homeland concept, alluded to in Britain's 1917 Balfour Declaration, they officially continued to "acquiesce". Throughout the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, the Departments of War and State recognized the possibility of a Soviet-Arab connection and the potential Arab restriction on Oil supplies to the US, and advised against U.S. intervention on behalf of the Jews.[12] With continuing conflict in the area and worsening humanitarian conditions among Holocaust survivors in Europe, on 29 November 1947 and with US support, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 181, the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, which was to create Jewish and Arab states and take effect upon British withdrawal. The decision was heavily lobbied by Zionist supporters, which Truman himself later noted,[13] and rejected by the Arabs.

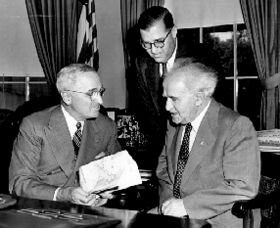

As the end of the mandate approached, the decision to recognize the Jewish state remained contentious, with significant disagreement between President Truman, his domestic and campaign adviser, Clark Clifford, and both the State Department and Defense Department. Truman, while sympathetic to the Zionist cause, was most concerned about relieving the plight of the displaced persons; Secretary of State George Marshall feared U.S. backing of a Jewish state would harm relations with the Muslim world, limit access to Middle Eastern oil, and destabilize the region. On May 12, 1948, Truman met in the Oval Office with Secretary of State Marshall, Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, Counsel to the President Clark Clifford and several others to discuss the Palestine situation. Clifford argued in favor of recognizing the new Jewish state in accordance with the partition resolution. Marshall opposed Clifford's arguments, contending they were based on domestic political considerations in the election year. Marshall said that if Truman followed Clifford's advice and recognized the Jewish state, then he would vote against Truman in the election. Truman did not clearly state his views in the meeting.[14] Two days later, on May 14, 1948, the United States, under Truman, became the first country to extend de facto recognition to the State of Israel, 11 minutes after it unilaterally declared itself independent. With this unexpected decision, US representative to the United Nations Warren Austin, whose team had been working on an alternative trusteeship proposal, shortly thereafter left his office at the UN and went home. Secretary of State Marshall sent a State Department official to the United Nations to prevent the entire United States delegation from resigning.[14] De jure recognition came on January 31, 1949.

Following UN mediation by American Ralph Bunche, the 1949 Armistice Agreements ended the 1948 Arab Israeli War. Related to enforcement of the armistice, the United States signed the Tripartite Declaration of 1950 with Britain and France. In it, they pledged to take action within and outside the United Nations to prevent violations of the frontiers or armistice lines, and outlined their commitment to peace and stability in the area, their opposition to the use or threat of force, and reiterated their opposition to the development of an arms race in the region.

Under rapidly changing geopolitical circumstances, U.S. policy in the Middle East generally, was geared toward supporting Arab states independence, the development of oil-producing countries, preventing Soviet influence from gaining a foothold in Greece, Turkey and Iran, as well as preventing an arms race and maintaining a neutral stance in the Arab-Israeli conflict. U.S. policymakers initially used foreign aid to support these objectives.

Foreign policy of U.S. government

Eisenhower Administration (1953-1961)

During these years of austerity, the United States provided Israel moderate amounts of economic aid, mostly as loans for basic food stuffs; a far greater share of state income derived from German war reparations, which were used for domestic development.

France became Israel's main arms supplier at this time and provided Israel with advanced military equipment and technology. This support was seen by Israel to counter the perceived threat from Egypt under President Gamal Abdel Nasser with respect to the "Czech arms deal" of September 1955. During the 1956 Suez Crisis for differing reasons, France, Israel and Britain colluded to topple Nasser by regaining control of the Suez Canal, following its nationalization, and to occupy parts of western Sinai assuring free passage of shipping in the Gulf of Aqaba.[15] In response, the U.S., with support from Soviet Union at the United Nations intervened on behalf of Egypt to force a withdrawal. Afterward, Nasser expressed a desire to establish closer relations with the United States. Eager to increase its influence in the region, and prevent Nasser from going over to the Soviet Bloc, U.S. policy was to remain neutral and not become too closely allied with Israel. In the early 1960s, the U.S. would begin to sell advanced, but defensive, weapons to Israel, Egypt and Jordan, including Hawk anti aircraft missiles.

Kennedy and Johnson administrations (1961–1969)

During Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency, U.S. policy shifted to a whole-hearted, but not unquestioning, support for Israel. Prior to the Six-Day War of 1967, U.S. administrations had taken considerable care to avoid giving the appearance of favoritism. Writing in American Presidents and the Middle East, George Lenczowski notes, "Johnson's was an unhappy, virtually tragic presidency", regarding "America's standing and posture in the Middle East", and marked a turning point in both U.S.-Israeli and U.S.-Arab relations.[16] He characterizes the Middle Eastern perception of the US as moving from "the most popular of Western countries" before 1948, to having "its glamour diminished, but Eisenhower's standing during the Arab-Israeli Suez Crisis convinced many Middle Eastern moderates that, if not actually lovable, the United States was at least a fair country to deal with; this view of U.S. fairness and impartiality still prevailed during Kennedy's presidency; but during Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency America's policy took a definite turn in the pro-Israeli direction. The June war of 1967 confirmed this impression, and from 1967 on [writing in 1990] the United States emerged as the most distrusted if not actually hated country in the Middle East."

Leading up to the war, while the Administration was sympathetic to Israel's need to defend itself against foreign attack, the U.S. worried that Israel's response would be disproportionate and potentially destabilizing. Israel's raid into Jordan after the Samu Incident was very troubling to the U.S. because Jordan was also an ally and had received over $500 million in aid for construction of the East Ghor Main Canal, which was virtually destroyed in subsequent raids.

The primary concern of the Johnson Administration was that should war break out in the region, the United States and Soviet Union would be drawn into it. Intense diplomatic negotiations with the nations in the region and the Soviets, including the first use of the Hotline, failed to prevent war. When Israel launched preemptive strikes against the Egyptian Air force, Secretary of State Dean Rusk was disappointed as he felt a diplomatic solution could have been possible.

In 1966, when a defecting Iraqi pilot landed in Israel flying a Soviet-built MiG-21 fighter jet, information on the plane was immediately shared with the United States.

During the war, Israeli warplanes and warships shot at the USS Liberty, a US Navy intelligence ship in Egyptian waters, killing 34 and wounding at least 173. Israel claimed the Liberty was mistaken as an Egyptian vessel and it was an instance of friendly fire, and the U.S. government accepted it as such. Following the war, the perception in Washington was that many Arab states (notably Egypt) had permanently drifted toward the Soviets. In 1968, with strong support from Congress, Johnson approved the sale of Phantom fighters to Israel, establishing the precedent for U.S. support for Israel's qualitative military edge over its neighbors. The U.S., however, continued to supply arms to Israel's neighbors, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, to counter Soviet arms sales in the region.

When the French government imposed an arms embargo on Israel in 1967, Israeli spies procured designs of the Dassault Mirage 5 from a Swiss-Jewish engineer in order to build the IAI Kfir. These designs were also shared with the United States.

Nixon and Ford Administrations (1969–1977)

Rogers Plan of 1970

On 19 June 1970, Secretary of State William P. Rogers formally proposed the Rogers Plan, which called for a 90 day cease-fire and a military standstill zone on each side of the Suez Canal, to calm the ongoing War of Attrition. It was an effort to reach agreement specifically on the framework of UN Resolution 242, which called for Israeli withdrawal from territories occupied in 1967 and mutual recognition of each state's sovereignty and independence.[17] The Egyptians accepted the Rogers Plan, but the Israelis were split and did not; they failed to get sufficient support within the 'unity government'. Despite the Labor-dominant Alignment's, formal acceptance of UN 242 and "peace for withdrawal" earlier that year, Menachen Begin and the right wing Gahal alliance were adamantly opposed to withdraw from the Palestinian Territories; the second-largest party in the government resigned on August 5, 1970.[18] Ultimately the plan also failed due to insufficient support from Nixon for his Secretary of State's plan, preferring instead the position of his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, not to pursue the initiative.

No breakthrough occurred even after President Sadat of Egypt in 1972 unexpectedly expelled Soviet advisers from Egypt, and again signaled to Washington his willingness to negotiate.[19] Faced with this lack of progress on the diplomatic front, and hoping to force the Nixon administration to become more involved, Egypt prepared for military conflict. In October 1973, Egypt and Syria, with additional Arab support, attacked Israeli forces occupying their territory since the 1967 war, thus starting the Yom Kippur War.

Despite intelligence indicating an attack from Egypt and Syria, Prime Minister Golda Meir made the controversial decision not to launch a pre-emptive strike. Meir, among other concerns, feared alienating the United States, which Israel was entirely dependent upon to resupply its military, if Israel was seen as starting another war. In retrospect, the decision not to strike was probably a sound one. Later, according to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, had Israel struck first, they would not have received "so much as a nail." Days into the war, Meir authorized the assembly of Israeli nuclear weapons for potential use,[20][21] the Soviets began to resupply their allies, predominantly Syria, and President Nixon ordered the full scale commencement of a strategic airlift operation to deliver weapons and supplies to Israel; this last move is sometimes called "the airlift that saved Israel."

Again, the U.S. and Soviets feared that they would be drawn into a Middle East conflict. After the Soviets threatened intervention on the behalf of Egypt, following Israeli advances beyond the cease-fire lines, the U.S. increased the Defense Condition (DEFCON) from four to three, the highest peacetime level. This was prompted after Israel trapped Egypt's Third Army east of the Suez canal.

Kissinger realized the situation presented the United States with a tremendous opportunity—Egypt was totally dependent on the U.S. to prevent Israel from destroying the army, which now had no access to food or water. The position could be parlayed later into allowing the United States to mediate the dispute, and push Egypt out of Soviet influences. As a result, the United States exerted tremendous pressure on the Israelis to refrain from destroying the trapped army. In a phone call with Israeli ambassador Simcha Dinitz, Kissinger told the ambassador that the destruction of the Egyptian Third Army "is an option that does not exist." The Egyptians later withdrew their request for support and the Soviets complied.

After the war, Kissinger pressured the Israelis to withdraw from Arab lands; this contributed to the first phases of a lasting Israeli-Egyptian peace. American support of Israel during the war contributed to the 1973 OPEC embargo against the United States, which was lifted in March 1974.

Carter administration (1977–1981)

The Jimmy Carter years were characterized by very active U.S. involvement in the Middle East peace process. With the May 1977 election of Likud'sMenachem Begin as prime minister, after 30 years of leading the Israeli government opposition, major changes took place regarding Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories.[2] This, in turn led to friction in U.S.-Israeli bilateral relations. The two frameworks included in the Carter-initiated Camp David process were viewed by right wing elements in Israel as creating U.S. pressures on Israel to withdraw from the captured Palestinian territories, as well as forcing it to take risks for the sake of peace with Egypt. Likud governments have since argued that their acceptance of full withdrawal from the Sinai as part of these accords and the eventual Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty fulfilled the Israeli pledge to withdraw from occupied territory.[2] President Carter's support for a Palestinian homeland and for Palestinian political rights particularly created tensions with the Likud government, and little progress was achieved on that front.

Reagan administration (1981–1989)

Israeli supporters expressed concerns early in the first Ronald Reagan term about potential difficulties in U.S.-Israeli relations, in part because several Presidential appointees had ties or past business associations with key Arab countries (Secretaries Caspar Weinberger and George P. Shultz, for example, were officers in the Bechtel Corporation, which has strong links to the Arab world, see Arab lobby in the United States.) But President Reagan's personal support for Israel and the compatibility between Israeli and Reagan perspectives on terrorism, security cooperation, and the Soviet threat, led to considerable strengthening in bilateral relations.

In 1981, Weinberger and Israeli Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon signed Strategic Cooperation Agreement, establishing a framework for continued consultation and cooperation to enhance the national security of both countries. In November 1983, the two sides formed a Joint Political Military Group, which meets twice a year, to implement most provisions of that agreement. Joint air and sea military exercises began in June 1984, and the United States has constructed two War Reserve Stock facilities in Israel to stockpile military equipment. Although intended for American forces in the Middle East, the equipment can be transferred to Israeli use if necessary.

U.S.-Israeli ties strengthened during the second Reagan term. Israel was granted "major non-NATO ally" status in 1989 that gave it access to expanded weapons systems and opportunities to bid on U.S. defense contracts. The United States maintained grant aid to Israel at $3 billion annually and implemented a free trade agreement in 1985. Since then all customs duties between the two trading partners have been eliminated. However, relations soured when Israel carried out Operation Opera, an Israeli airstrike on the Osirak nuclear reactor in Baghdad. Reagan suspended a shipment of military aircraft to Israel, and harshly criticized the action. Relations also soured during the 1982 Lebanon War, when the United States even contemplated sanctions to stop the Israeli Siege of Beirut. The U.S. reminded Israel that weaponry provided by the U.S. was to be used for defensive purposes only, and suspended shipments of cluster munitions to Israel. Although the war exposed some serious differences between Israeli and U.S. policies, such as Israel's rejection of the Reagan peace plan of September 1, 1982, it did not alter the Administration's favoritism for Israel and the emphasis it placed on Israel's importance to the United States. Although critical of Israeli actions, the United States vetoed a Soviet-proposed United Nations Security Council resolution to impose an arms embargo on Israel.

In 1985, the U.S. supported Israel's economic stabilization through roughly $1.5 billion in two-year loan guarantees the creation of a U.S.-Israel bilateral economic forum called the U.S.-Israel Joint Economic Development Group (JEDG).

In November 1985, Jonathan Pollard, a civilian U.S. naval intelligence employee, and his wife were charged with selling classified documents to Israel. Four Israeli officials also were indicted. The Israeli government claimed that it was a rogue operation. Pollard was sentenced to life in prison and his wife to two consecutive five-year terms. Israelis complain that Pollard received an excessively harsh sentence, and some Israelis have made a cause of his plight. Pollard was granted Israeli citizenship in 1996, and Israeli officials periodically raise the Pollard case with U.S. counterparts, although there is not a formal request for clemency pending.

The second Reagan term ended on what many Israelis considered to be a sour note when the United States opened a dialogue with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in December 1988. But, despite the US-PLO dialogue, the Pollard spy case, or the Israeli rejection of the Shultz peace initiative in the spring of 1988, pro-Israeli organizations in the United States characterized the Reagan Administration (and the 100th Congress) as the "most pro-Israel ever" and praised the positive overall tone of bilateral relations.

Bush administration (1989–1993)

Secretary of State James Baker told an American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC, a pro-Israel lobby group) audience on May 22, 1989, that Israel should abandon its "expansionist policies," a remark many took as a signal that the relatively pro-Israel Reagan years were over. President Bush raised the ire of the Likud government when he told a press conference on March 3, 1990, that East Jerusalem was occupied territory and not a sovereign part of Israel as Israel claims. Israel had annexed East Jerusalem in 1980, an action which did not gain international recognition. The United States and Israel disagreed over the Israeli interpretation of the Israeli plan to hold elections for a Palestinian peace conference delegation in the summer of 1989, and also disagreed over the need for an investigation of the Jerusalem incident of October 8, 1990, in which Israeli police killed 17 Palestinians.

Amid the Iraq-Kuwait crisis and Iraqi threats against Israel generated by it, former President Bush repeated the U.S. commitment to Israel's security. Israeli-U.S. tension eased after the start of the Persian Gulf war on January 16, 1991, when Israel became a target of Iraqi Scud missiles. The United States urged Israel not to retaliate against Iraq for the attacks because it was believed that Iraq wanted to draw Israel into the conflict and force other coalition members, Egypt and Syria in particular, to quit the coalition and join Iraq in a war against Israel. Israel did not retaliate, and gained praise for its restraint.

Following the Gulf War, the administration immediately returned to Arab-Israeli peacemaking, believing there was a window of opportunity to use the political capital generated by the U.S. victory to revitalize the Arab-Israeli peace process. On 6 March 1991, President Bush addressed Congress in a speech often cited as the administration’s principal policy statement on the new order in relation to the Middle East, following the expulsion of Iraqi forces from Kuwait.[22][23] Michael Oren summarizes the speech, saying: “The president proceeded to outline his plan for maintaining a permanent U.S. naval presence in the Gulf, for providing funds for Middle East development, and for instituting safeguards against the spread of unconventional weapons. The centerpiece of his program, however, was the achievement of an Arab-Israeli treaty based on the territory-for-peace principle and the fulfillment of Palestinian rights.” As a first step Bush announced his intention to reconvene the international peace conference in Madrid.[22]

Unlike earlier American peace efforts however, no new aid commitments would be used. This was both because President Bush and Secretary Baker felt the coalition victory and increased U.S. prestige would itself induce a new Arab-Israeli dialogue, and because their diplomatic initiative focused on process and procedure rather than on agreements and concessions. From Washington's perspective, economic inducements would not be necessary, but these did enter the process because Israel injected them in May. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir's request for $10 billion in U.S. loan guarantees added a new dimension to U.S. diplomacy and sparked a political showdown between his government and the Bush administration.[24]

Bush and Baker were thus instrumental in convening the Madrid peace conference in October 1991 and in persuading all the parties to engage in the subsequent peace negotiations. It was reported widely that the Bush Administration did not share an amicable relationship with the Likud government of Yitzhak Shamir. The Israeli government however, did win the repeal of UN Resolution 3379, which equated Zionist with racism. After the conference, in December 1991, the UN passed United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/86; Israel had made revocation of resolution 3379 a condition of its participation in the Madrid peace conference.[25] After the Labor party won the 1992 election, U.S.-Israel relations appeared to improve. The Labor coalition approved a partial housing construction freeze in the occupied territories on July 19, something the Shamir government had not done despite Bush Administration appeals for a freeze as a condition for the loan guarantees.

Clinton administration (1993–2001)

Israel and the PLO exchanged letters of mutual recognition on September 10, and signed the Declaration of Principles on September 13, 1993. President Bill Clinton announced on September 10 that the United States and the PLO would reestablish their dialogue. On October 26, 1994, President Clinton witnessed the Jordan-Israeli peace treaty signing, and President Clinton, Egyptian President Mubarak, and King Hussein of Jordan witnessed the White House signing of the September 28, 1995 Interim Agreement between Israel and the Palestinians.

President Clinton attended the funeral of assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in Jerusalem in November, 1995. Following a March, 1996 visit to Israel, President Clinton offered $100 million in aid for Israel's anti-terror activities, another $200 million for Arrow anti-missile deployment, and about $50 million for an anti-missile laser weapon. President Clinton disagreed with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's policy of expanding Jewish settlements in the occupied territories, and it was reported that the President believed that the Prime Minister delayed the peace process. President Clinton hosted negotiations at the Wye River Conference Center in Maryland, ending with the signing of an agreement on October 23, 1998. Israel suspended implementation of the Wye agreement in early December 1998, when the Palestinians violated the Wye Agreement by threatening to declare a state (Palestinian statehood was not mentioned in Wye). In January 1999, the Wye Agreement was delayed until the Israeli elections in May.

Ehud Barak was elected Prime Minister on May 17, 1999, and won a vote of confidence for his government on July 6, 1999. President Clinton and Prime Minister Barak appeared to establish close personal relations during four days of meetings between July 15 and 20. President Clinton mediated meetings between Prime Minister Barak and Chairman Arafat at the White House, Oslo, Shepherdstown, Camp David, and Sharm al-Shaykh in the search for peace.

Bush administration (2001–2009)

President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Sharon established good relations in their March and June 2001 meetings. On October 4, 2001, shortly after the 9/11 attacks, Sharon accused the Bush Administration of appeasing the Palestinians at Israel's expense in a bid for Arab support for the U. S. anti-terror campaign. The White House said the remark was unacceptable. Rather than apologize for the remark, Sharon said the United States failed to understand him. Also, the United States criticized the Israeli practice of assassinating Palestinians believed to be engaged in terrorism, which appeared to some Israelis to be inconsistent with the U.S. policy of pursuing Osama bin Laden "dead or alive."

In 2003, on the heels of the Second Intifada and a sharp economic downturn in Israel, the U.S. provided Israel with $9 billion in conditional loan guarantees made available through 2011 and negotiated each year at the U.S.-Israel Joint Economic Development Group (JEDG).

All recent U.S. administrations have disapproved of Israel's settlement activity as prejudging final status and possibly preventing the emergence of a contiguous Palestinian state. President Bush, however noted the need to take into account changed "realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli population centers," asserting "it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949." He later emphasized that it was a subject for negotiations between the parties.

At times of violence, U.S. officials have urged Israel to withdraw as rapidly as possible from Palestinian areas retaken in security operations. The Bush Administration insisted that United Nations Security Council resolutions be "balanced," by criticizing Palestinian as well as Israeli violence and has vetoed resolutions which do not meet that standard.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has not named a Special Middle East Envoy and has said that she will not get involved in direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiations of issues. She says that she prefers to have the Israelis and Palestinians work together, although she has traveled to the region several times in 2005. The Administration supported Israel's disengagement from Gaza as a way to return to the Road Map process to achieve a solution based on two states, Israel and Palestine, living side by side in peace and security. The evacuation of settlers from the Gaza Strip and four small settlements in the northern West Bank was completed on August 23, 2005.

During 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict

Military Relations

On July 14 2006, the US Congress was notified of a potential sale of $210 million worth of jet fuel to Israel. The Defense Security Cooperation Agency noted that the sale of the JP-8 fuel, should it be completed, will "enable Israel to maintain the operational capability of its aircraft inventory." and "The jet fuel will be consumed while the aircraft is in use to keep peace and security in the region."[26] It was reported in 24 July that the United States was in the process of providing Israel with "bunker buster" bombs, which would allegedly be used to target the leader of Lebanon's Hezbollah guerilla group and destroy its trenches.[27]

American media also questioned whether Israel violated an agreement not to use cluster bombs on civilian targets. Although many of the cluster bombs used were advanced M-85 munitions developed by Israel Military Industries, Israel also used older munitions purchased from the U.S. Evidence during the conflict had shown that cluster bombs had hit civilian areas, although the civilian population had mostly fled, as well as Israel claiming that Hezbollah frequently used civilian areas for military activity. Many bomblets remained undetonated after the war, causing hazard for Lebanese civilians. Israel said that it had not violated any international law because cluster bombs are not illegal and were used only on military targets.[28]

Opposing immediate unconditional ceasefire

On July 15, the United Nations Security Council again rejected pleas from Lebanon that it call for an immediate ceasefire between Israel and Lebanon. The Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported the U.S. was the only member of out the 15-nation UN body to oppose any council action at all.[29]

On July 19, the Bush administration rejected calls for an immediate ceasefire.[30] Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said certain conditions had to be met, not specifying what they were. John Bolton, then U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, rejected the call for a ceasefire, on the grounds that such an action addressed the conflict only superficially: "The notion that you just declare a ceasefire and act as if that is going to solve the problem, I think is simplistic."[31]

On July 26, foreign ministers from the United States, Europe and the Middle East that met in Rome vowed "to work immediately to reach with the utmost urgency a ceasefire that puts an end to the current violence and hostilities," though the US maintained strong support for the Israeli campaign and the conference's results were reported to have fallen short of Arab and European leaders' expectations.[32]

Strained relations under Benjamin Netanyahu and Barack Obama

Israeli-US relations came under increased strain during Prime Minister Netanyahu's second administration and the new Obama administration in March 2010, when Israel announced it would continue to build 1,600 new homes that were already under construction in a Jewish area of East Jerusalem, during Vice-President Joe Biden's visit to Israel. The incident was described as "one of the most serious rows between the two allies in recent decades".[33] Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said Israel's move was "deeply negative" for US-Israeli relations.[34] East Jerusalem is, on the international diplomatic stage, widely considered to be occupied territory—building on occupied land is illegal under international law.[33] Israel disputes this, as it annexed East Jerusalem and proclaimed the city as its capital in 1980, under the Jerusalem Law.

Current issues

United States military and economic aid

Since the 1970s, Israel has been one of the top recipients of U.S. foreign aid.[36] While it is mostly military aid, in the past a portion was dedicated to economic assistance, but all economic aid to Israel ended in 2007. In 2004, the second-largest recipient of economic foreign aid from the United States was Israel, second to post-war Iraq. In terms of per capita value Israel ranks first, though other middle eastern countries get US aid as well — Egypt gets around $2.2 billion per year, Jordan gets around $400 million per year, and the Palestinian Authority gets around $1 billion per year.[37]

In 2007, the United States increased its military aid to Israel by over 25% to an average of $3 billion per year for the following ten year period. The United States ended economic aid to Israel in 2007, due to Israel's growing economy.[38][39]

In 1998, Israeli, congressional, and Administration officials agreed to reduce U.S. $1.2 billion in Economic Support Funds (ESF) to zero over ten years, while increasing Foreign Military Financing (FMF) from $1.8 billion to $2.4 billion. Separate from the scheduled cuts, there was an extra $200 million in anti-terror assistance, $1.2 billion to implement the Wye agreement, and the supplemental appropriations bill assisted for another $1 billion in FMF for the 2003 fiscal year. For the 2005 fiscal year, Israel received $2.202 billion in FMF, $357 million in ESF, and migration settlement assistance of $50 million. For 2006, the Administration has requested $240 million in ESF and $2.28 billion in FMF. H.R. 3057, passed in the House on June 28, 2005, and in the Senate on July 20, approved these amounts. House and Senate measures also supported $40 million for the settlement of immigrants from the former Soviet Union and plan to bring the remaining Ethiopian Jews to Israel.

Israeli press reported that Israel requested $2.25 billion in special aid in a mix of grants and loan guarantees over four years, with one-third to be used to relocate military bases from the Gaza Strip to Israel in the disengagement from the Gaza Strip and the rest to develop the Negev and Galilee regions of Israel and for other purposes, but none to help compensate settlers or for other civilian aspects of the disengagement. An Israeli team has visited Washington to present elements of the request, and preliminary discussions are underway. No formal request has been presented to Congress. In light of the costs inflicted on the United States by Hurricane Katrina, an Israeli delegation intending to discuss the aid canceled a trip to Washington.

Congress has legislated other special provisions regarding aid to Israel. Since the 1980s, ESF and FMF have been provided as all grant cash transfers, not designated for particular projects, transferred as a lump sum in the first month of the fiscal year, instead of in periodic increments. Israel is allowed to spend about one-quarter of the military aid for the procurement in Israel of defense articles and services, including research and development, rather than in the United States. Finally, to help Israel out of its economic slump, the U.S. provided $9 billion in loan guarantees over three years, use of which was extended to 2008.

President Obama's Fiscal Year 2010 budget proposes $53.8 billion for appropriated international affairs' programs. From that budget, $5.7 billion is appopriated for foreign military financing, military education, and peacekeeping operations. From that $5.7 billion, $2.8 billion, almost 50% is appropriated for Israel.[40] Israel also has available roughly $3 billion of conditional loan guarantees, with additional funds coming available if Israel meets conditions negotiated at the U.S.-Israel Joint Economic Development Group (JEDG).

Washington pressures against peace talks with Syria

Syria has repeatedly requested that Israel re-commence peace negotiations with the Syrian government.[41] There is an on-going internal debate within the Israeli government regarding the seriousness of this Syrian invitation for negotiations. Some Israeli officials asserted that there had been some unpublicized talks with Syria not officially sanctioned by the Israeli government.[42][43][44]

The United States demanded that Israel desist from even exploratory contacts with Syria to test whether Damascus is serious in its declared intentions to hold peace talks with Israel. U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice was forceful in expressing Washington's view on the matter to Israeli officials that even exploratory negotiations with Syria must not be attempted. For years, Israel obeyed Washington's demand to desist from officially returning to peace talks.[45][46] Around May 2008 however, Israel informed the U.S. that it was starting peace talks with Syria brokered by Turkey. However, Syria withdrew from the peace talks several months later in response to the Gaza War.

Military sales to China

Over the years, the United States and Israel have regularly discussed Israel's sale of sensitive security equipment and technology to various countries, especially the People's Republic of China. U.S. administrations believe that such sales are potentially harmful to the security of U.S. forces in Asia. China has looked to Israel to obtain technology it could not aquire from elsewhere, and has purchased a wide array of military equipment and technology, including communications satellites. To further foster its relationship with China, Israel has strongly limited its cooperation with Taiwan. In 2000, the United States persuaded Israel to cancel the sale of the Phalcon, an advanced, airborne early-warning system developed by Israel Aircraft Industries, to China. In 2005, the U.S. Department of Defense was angered by Israel's agreement to upgrade Harpy Killer unmanned aerial vehicles, which it had sold to China in 1999, and which China tested over the Taiwan Strait in 2004. The Department suspended technological cooperation with the Israeli Air Force on the future F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) aircraft as well as several other cooperative programs, held up shipments of some military equipment, and refused to communicate with Israeli Defense Ministry Director, General Amos Yaron, whom Pentagon officials believe misled them about the Harpy deal. According to a reputable Israeli military journalist the U.S. Department of Defense demanded details of 60 Israeli deals with China, an examination of Israel's security equipment supervision system, and a memorandum of understanding about arms sales to prevent future difficulties.

Maintenance contract with Venezuela

On October 21, 2005, it was reported that pressure from Washington forced Israel to freeze a major contract with Venezuela to upgrade its 22 U.S.-manufactured F-16 fighter jets. The Israeli government had requested U.S. permission to proceed with the deal, but permission has not been granted.[47]

Jerusalem

Since capturing East Jerusalem in the 1967 Six Day War, Israel has insisted that Jerusalem is its eternal and indivisible capital. The United States does not agree with this position and believes the permanent status of Jerusalem is still subject to negotiations. This is based on the UN's 1947 Partition plan for Palestine, which called for separate international administration of Jerusalem. This position was accepted at the time by most other countries and the Zionist leadership, but rejected by the Arab countries. As a result, most countries had located their embassies in Tel Aviv before 1967; Jerusalem was also located on the contested border. The Declaration of Principles and subsequent Oslo Accords signed between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization in September 1993 similarly state that it is a subject for permanent status negotiations. U.S. Administrations have consistently indicated, by keeping the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv, that Jerusalem's status is unresolved.

In 1995, however, both houses of Congress overwhelmingly passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act to move the embassy to Jerusalem, no later than May 31, 1999, and suggested funding penalties on the State Department for non-compliance. Executive Branch opposition to such a move, on constitutional questions of Congressional interference in foreign policy, as well as a series of presidential waivers, based on national security interests, have delayed the move by all successive administrations, since it was passed during the Clinton Administration.[48]

The U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem was first established in 1844, just inside the Jaffa Gate. A permanent consular office was established in 1856 in this same building. The mission moved to Street of the Prophets in the late 19th century, and to its present location on Agron Street in 1912. The Consulate General on Nablus Road in East Jerusalem was built in 1868 by the Vester family, the owners of the American Colony Hotel. In 2006, the U.S. Consulate General on Agron Road leased an adjacent building, a Lazarist monastery built in the 1860s, to provide more office space.[49]

In March 2010 Gen. David Petraeus was quoted by Max Boot claiming the lack of progress in the Middle East peace process has "fomented anti-Americanism, undermined moderate Arab regimes, limited the strength and depth of U.S. partnerships, increased the influence of Iran, projected an image of U.S. weakness, and served as a potent recruiting tool for Al Qaeda."[50] When questioned by journalist Philip Klein, Petraeus said Boot "picked apart" and "spun" his speech. He believes there are many important factors standing in the way of peace, including “a whole bunch of extremist organizations, some of which by the way deny Israel’s right to exist. There’s a country that has a nuclear program who denies that the Holocaust took place. So again we have all these factors in there. This [Israel] is just one."[51]

US-Israeli relations came under strain in March 2010, as Israel announced it was building 1,600 new homes in occupied East Jerusalem as Vice President Joe Biden was visiting.[52] Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described the move as "insulting".[52]

Public opinion

Poll results fluctuate every year, although both sides of sympathy have modestly stepped up since 1998 and those with no preference have modestly decreased. The greatest percentage consistently sympathize with Israel (Gallup Poll). The September 11, 2001 attacks and 2006 Israel-Hezbollah War both saw heights in American sympathy for Israel, with most Americans putting the blame on Hezbollah for the war and the civilian casualties.[5] The record-breaking height of sympathy for Israel was during the 1991 Gulf War, as well as the all-time low of sympathy for the Palestinians, whose leadership supported Saddam Hussein.[53]

As of July 2006, polls claimed that 44% of Americans thought that the "United States supports Israel about the right amount," 11% thought "too little", and 38% thought "too much".[54][55][56][57] Many in the United States question the levels of aid and general commitment to Israel, and argue that a U.S. bias operates at the expense of improved relations with various Arab states. Others maintain that democratic Israel is a helpful and strategic ally, and believe that U.S. relations with Israel strengthen the U.S. presence in the Middle East.[58] A 2002–2006 Gallup Poll of Americans by party affiliation (Republican/Democratic) and ideology (conservative/moderate/liberal) found that although sympathy for Israel is strongest amongst the right (conservative Republicans), the group most on the left (liberal Democrats) also have a greater percentage sympathizing with Israel. Although proportions are different, each group has most sympathizing more with Israel, followed by both/neither, and lastly more with the Palestinians.[6]. Gallup's Feb. 1–4 World Affairs poll included the annual update on Americans' ratings of various countries around the world, and asked Americans to rate the overall importance to the United States of what happens in most of these nations. According to one 2007 poll, Israel was the only country that a majority of Americans felt favorably toward and said that what happens there is vitally important to the United States.[7]

Israeli attitudes toward the U.S. are largely positive. In several ways of measuring a country's view of America (American ideas about democracy; ways of doing business; music, movies and television; science and technology; spread of U.S. ideas), Israel came on top as the developed country who viewed it most positively.[8]

Immigration

Israel is in large part a nation of immigrants. Israel has welcomed newcomers inspired by Zionism, the Jewish national movement. Zionism is an expression of the desire of many Jews to live in a historical homeland. The largest numbers of immigrants have come to Israel from countries in the Middle East and Europe.

The United States has played a special role in assisting Israel with the complex task of absorbing and assimilating masses of immigrants in short periods of time. Soon after Israel's establishment, President Truman offered $135 million in loans to help Israel cope with the arrival of thousands of refugees from the Holocaust. Within the first three years of Israel's establishment, the number of immigrants more than doubled the Jewish population of the country.

Mass immigrations have continued throughout Israeli history. Since 1989, Israel absorbed approximately one million Jews from the former Soviet Union. The United States worked with Israel to bring Jews from Arab countries, Ethiopia and the former Soviet Union to Israel, and has assisted in their absorption into Israeli society.

Economy

The cornerstone of the vibrant U.S.-Israel economic relationship is the 1985 Free Trade Agreement (FTA), the first FTA ever signed by the United States. Over the last 20 years the FTA has enabled a sevenfold expansion of bilateral trade. Israel has become one of the largest trading partners of the U.S. in the Middle East and Israel's prime export destination is the United States. The U.S. and Israel also discuss fiscal and other possible macroeconomic reforms as part of the annual U.S.-Israel Joint Economic Development Group (JEDG) meeting, as well as negotiate terms for remaining guarantees to be disbursed from the $9 billion in loan guarantees allotted to Israel in 2003.

Corporate exchange

Several regional America-Israel Chambers of Commerce exist to facilitate expansion by Israeli and American companies into each other's markets.[59] American companies such as Motorola, IBM, Microsoft and Intel chose Israel to establish major R&D centers. Israel has more companies listed on the NASDAQ than any country outside North America.

Strategic cooperation

The U.S. and Israel are engaged in extensive strategic, political and military cooperation. This cooperation is broad and includes American aid, intelligence sharing and joint military exercises. American military aid to Israel comes in different forms, including grants, special project allocations and loans.

Memorandum of Understanding

To address threats to security in the Middle East, including joint military exercises and readiness activities, cooperation in defense trade and access to maintenance facilities. The signing of the Memorandum of Understanding marked the beginning of close security cooperation and coordination between the American and Israeli governments. Comprehensive cooperation between Israel and the United States on security issues became official in 1981 when Israel's Defense Minister Ariel Sharon and American Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger signed a Memorandum of Understanding that recognized "the common bonds of friendship between the United States and Israel and builds on the mutual security relationship that exists between the two nations." The memorandum called for several measures.

Missile program

One facet of the U.S.-Israel strategic relationship is the joint development of the Arrow Anti-Ballistic Missile Program. Designed to intercept and destroy ballistic missiles, the Arrow is the most advanced missile defense system in the world. The development is funded by both Israel and the United States. The Arrow has also provided the U.S. the research and experience necessary to develop additional weapons systems.

Counter-terrorism

In April 1996, President Bill Clinton and Prime Minister Shimon Peres signed the U.S.-Israel Counter-terrorism Accord. The two countries agreed to further cooperation in information sharing, training, investigations, research and development and policymaking.

Homeland security

At the federal, state and local levels there is close Israeli-American cooperation on Homeland Security. Israel was one of the first countries to cooperate with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in developing initiatives to enhance homeland security. In this framework, there are many areas of partnership, including preparedness and protection of travel and trade. American and Israeli law enforcement officers and Homeland Security officials regularly meet in both countries to study counter-terrorism techniques and new ideas regarding intelligence gathering and threat prevention.

In December 2005, the United States and Israel signed an agreement to begin a joint effort to detect the smuggling of nuclear and other radioactive material by installing special equipment in Haifa, Israel's busiest seaport. This effort is part of a nonproliferation program of the U.S. Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration that works with foreign partners to detect, deter, and interdict illicit trafficking in nuclear and other radioactive materials.

See also

- America-Israel Friendship League

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Foreign relations of Israel

- United States Ambassador to Israel

- USS Liberty incident

- Israel lobby in the United States

- Arab lobby in the United States

- The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy

- AIPAC

References

- ↑ U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel (Adapted from the summary of a report by Jeremy M. Sharp, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs, December 4, 2009) [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Israeli-United States Relations (Adapted from a report by Clyde R. Mark, Congressional Research Service, Updated October 17, 2002) [2]

- ↑ Patriot, Judge, and Zionist

- ↑ Jeffrey S. Gurock, American Zionism: mission and politics, p144, citing Jacob De Haas, Louis D. Brandeis (New York: 1929) and Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error (Philadelphia:1949). v.I, p.165

- ↑ Walworth (1986) 473-83, esp. p. 481; Melvin I. Urofsky, American Zionism from Herzl to the Holocaust, (1995) ch. 6; Frank W. Brecher, Reluctant Ally: United States Foreign Policy toward the Jews from Wilson to Roosevelt. (1991) ch 1-4.

- ↑ Walter John Raymond, Dictionary of politics: selected American and foreign political and legal terms, p287

- ↑ John Norton Moore, ed., The Arab Israeli Conflict III: Documents, American Society of International Law (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1974), p 107-8

- ↑ Rubenberg, Cheryl (1986). Israel and the American National Interest: A Critical Examination. University of Illinois Press. pp. 27. ISBN 0-252-06074-1.

- ↑ American Jewish Year Book Vol. 45 (1943-1944) Pro-Palestine and Zionist Activities, pp 206-214

- ↑ Michael Oren, Power, Faith and Fantasy, Decision at Biltmore, pp 442-445: Convening in the art deco dining halls of New York’s Biltmore Hotel in May 1942, Zionist representatives approved an eight point plan that, for the first time, explicitly called for the creation of a “Jewish Commonwealth integrated in the structure of the new democratic world.” Gone were the proposals for an amorphous Jewish national home in Palestine, for carving out Jewish cantons and delineating autonomous regions with and over arching Arab state. Similarly, effaced was the long-standing Zionist assumption that Palestine's fate would be decided in London. Instead, the the delegates agreed that the United States constituted the new Zionist “battleground” and that Washington would have the paramount say in the struggle for Jewish sovereignty. Henceforth the Zionist movement would strive for unqualified Jewish independence in Palestine, for a state with recognized borders, republican institutions, and a sovereign Army, to be attained in cooperation with America.

- ↑ Lenczowski, George (1990). American Presidents and the Middle East. Duke University Press. pp. 6. ISBN 0-8223-0972-6.

- ↑ Truman LibraryThe United States and the Recognition of Israel: Background

- ↑ Lenczowski, American Presidents and the Middle East, p. 28, cite, Harry S. Truman, Memoirs 2, p. 158. The facts were that not only were there pressure movements around the United Nations unlike anything that had been seen there before, but that the White House, too, was subjected to a constant barrage. I do not think I ever had as much pressure and propaganda aimed at the White House as I had in this instance. The persistence of a few of the extreme Zionist leaders — actuated by a political motive and engaging in political threats — disturbed and annoyed me.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Truman LibraryThe United States and the Recognition of Israel: A Chronology

- ↑ Avi Shlaim, The Protocol of Sèvres,1956: Anatomy of a War Plot Published in International Affairs, 73:3 (1997), 509-530

- ↑ George Lenczowski, American Presidents and the Middle East, Duke University Press, 1990, p.105-115

- ↑ “The Ceasefire/Standstill Proposal” 19 June 1970, http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.nsf/db942872b9eae454852560f6005a76fb/3e33d676ae43229b85256e60007086fd!OpenDocument last visited 2007/6/11

- ↑ William B. Quandt, Peace Process, American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict since 1967, p194, and ff. Begin himself explained Gahal's resignation from the government, saying "As far as we are concerned, what do the words 'withdrawal from territories administered since 1967 by Israel' mean other than Judea and Samaria. Not all the territories; but by all opinion, most of them."

- ↑ “The Camp David Accords: A Case of International Bargaining” Shibley Telhami, Columbia International Affairs Online, http://www.ciaonet.org/casestudy/tes01/index.html, last visited 2007/6/11

- ↑ Cohen, Avner. "The Last Nuclear Moment" The New York Times, 6 October 2003.

- ↑ Farr, Warner D. "The Third Temple's Holy of Holies: Israel's Nuclear Weapons." Counterproliferation Paper No. 2, USAF Counterproliferation Center, Air War College, September 1999.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Michael Oren, Power, Faith and Fanatsy, p569

- ↑ ‘New World Order’

- ↑ Scott Lasensky, Underwriting Peace in the Middle East: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Limits of Economic Inducements, Middle East Review of International Affairs: Volume 6, No. 1 - March 2002

- ↑ 260 General Assembly Resolution 46-86- Revocation of Resolution 3379- 16 December 1991- and statement by President Herzog, 16 Dec 1991 VOLUME 11-12: 1988-1992 and statement by President Herzog, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs web site.

- ↑ Defense Security Cooperation Agency news release 14 July 2006, Transmittal No. 06-40, [3]

- ↑ Israel to get U.S. "bunker buster" bombs - report, Reuters, 24 July 2006

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Middle East | US probes Israel cluster bomb use

- ↑ "Headlines for July 17, 2006". Democracy Now!. http://www.democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=06/07/17/1423239.

- ↑ "Headlines for July 19, 2006". Democracy Now!. 19 July 2006. http://www.democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=06/07/19/1345246.

- ↑ "Headlines for July 20, 2006". Democracy Now!. http://www.democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=06/07/20/1434244.

- ↑ "Rome talks yield no plan to end Lebanon fighting". Reuters. 2006-07-26. http://today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=topNews&storyID=2006-07-26T185440Z_01_L26848349_RTRUKOC_0_US-MIDEAST-MEETING.xml.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/8585239.stm

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/8565455.stm

- ↑ U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel. Congressional Research Service report for Congress. Jan 2, 2008. By Jeremy M. Sharp.

- ↑ U.S. Military Assistance and Arms Transfers to Israel, World Policy Institute.

- ↑ Tarnoff, Curt; Nowels, Larry (2004), Foreign Aid: An Introductory Overview of U.S. Programs and Policy, State Department, pp. 12–13, 98-916, http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/31987.pdf, retrieved 2008-03-04

- ↑ Forbes (July 29, 2007).[4]"Israeli PM announces 30 billion US dollar US defence aid". Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ↑ New York Times, August 17, 2007 "US and Israel sign Military deal".Retrieved Aug 17, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/

- ↑ The Times (UK), December 20, 2006, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article758520.ece , last visited Feb. 26, 2007

- ↑ "Syrians and Israelis 'held talks'," BBC, 1/16/07

- ↑ "Syrian, Israeli backdoor talks now emerging," Christian Science Monitor, 1/18/07

- ↑ "Why can't they just make peace?," Economist, 1/18/07

- ↑ Haaretz, February 24, 2007, http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/829441.html last visited Feb. 26/07

- ↑ The Times (UK), December 20, 2006, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article758520.ece last visited Feb. 26, 2007

- ↑ DefenseNews.com - U.S. Forced Israel to Freeze Venezuelan F-16 Contract: Ministry - 10/21/05 10:01

- ↑ Background: Gilo is not a settlement

- ↑ About the U.S. Consulate

- ↑ Petraeus Throws His Weight Into Middle East Debate

- ↑ http://www.commentarymagazine.com/blogs/index.php/boot/265971

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Bowen, Jeremy (May 9, 2010). "Analysis: Bleak climate for Mid-East talks". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/8660471.stm. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ↑ http://hrw.org/reports/2003/iraqjordan/Iraqjordan0503-03.htm

- ↑ PollingReport compilation

- ↑ CBS NEWS POLL: FIGHTING IN THE MIDDLE EAST

- ↑ Thoughts on aid

- ↑ New Poll Shows Strong and Stable U.S. Support for Israel in Third Week of Conflict with Iran-Backed Hezbollah

- ↑ Israel, the Palestinians....

- ↑ http://www.israeltrade.org/

)

Tarnoff, Curt; Nowels, Larry (2004), "Face recog…", Foreign Aid: An Introductory Overview of U.S. Programs and Policy, State Department, pp. 12–13, state-dept-report-foreign-aid-2004, http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/31987.pdf

Bibliography

- "Israeli-United States Relations" Almanac of Policy Issues

- Ball, George W. and Douglas B. Ball. The Passionate Attachment: America's Involvement With Israel, 1947 to the Present. New York: W.W. Norton, 1992. (ISBN 0-393-02933-6)

External links

- Israel and the United States: Friends, Partners, Allies

- Israeli–United States Relations Congressional Research Service

- Origins of the US-Israeli Strategic Partnership

- Israeli Embassy in Washington,D.C. page on U.S.-Israel relations

- United States Embassy in Israel

- Israel: Background and Relations with the United States CRS Report for Congress

- Israeli–United States Relations Policy Almanac

- U.S. rejects Israeli request to join visa waiver plan by Aluf Benn, Haaretz, February 19, 2006

- How Special is the U.S.-Israel relationship?

- Address by PM Olmert to a Joint Meeting of the U.S. Congress

- President Bush Meets with Bipartisan Members of Congress on the G8 Summit Transcript

- President Discusses Foreign Policy During Visit to State Department Transcript

- President Bush and Prime Minister Ehud Olmert of Israel Participate in Joint Press Availability Transcript

- U.S.-Israel Relations

- Coming Moment of Truth between Israel and the US by Gidi Grinstein Reut Institute

- Vital Support: Aid to Israel and US National Security Interests

- A Crisis in U.S.-Israel Relations: Have We Been Here Before? Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||